Atraumatic Spinal Compression Fractures

Am I allowed to say that figuring out atraumatic back pain is a pain in the behind? While the differential diagnosis is wide and we can’t forget all of the life-threatening causes of back pain, atraumatic spinal compression fractures remain among the differential. These fractures can present subtly, without any clear injury, which means urgent care clinicians need a high index of suspicion.

Who’s at risk?

Atraumatic spinal compression fractures occur most often in postmenopausal women with osteopenia or osteoporosis. Risk increases with age, low bone density, a history of prior compression fracture, chronic corticosteroid use, tobacco use, and certain medications that weaken bone.

A thorough history should include onset, location, severity, functional impact, prior spine issues, and risk factors for bone loss. Asking the patient to point with one finger to the area of greatest pain can help localize the problem. Reviewing their osteoporosis history, prior fractures, and relevant medications is important.

What do these patients often look like?

Patients may present with sudden-onset midline back pain after minimal stress, like bending or lifting something light. That said, over two-thirds of compression fractures are discovered incidentally on imaging, meaning many patients experience little or no pain.

The thoracolumbar junction, especially T12–L1, is the most common site. Its position between the rigid thoracic spine and the more mobile lumbar spine makes it prone to stress during movement. When pain is present, it tends to be localized, worsens with standing or walking, and improves with rest.

Neurological symptoms are uncommon in isolated compression fractures, but when present, they raise concern for retropulsion of bone fragments into the spinal canal and require prompt evaluation.

Key tips for physical exam and workup

Start with functional observation: watch how the patient rises from a chair and walks across the room. Then assess active spinal range of motion—flexion, extension, rotation, and side bending—as tolerated.

Palpate the spinous processes and paraspinal muscles for focal tenderness. It may be difficult to identify the exact vertebral level, but try to categorize it into cervical, thoracic, or lumbar. A focused neurological exam assessing lower limb strength, sensation, and reflexes is essential to rule out the red flags of back pain.

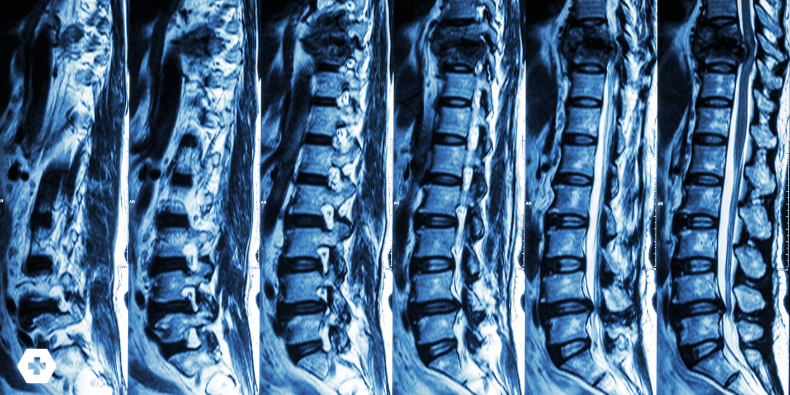

For most suspected cases, plain AP and lateral spine radiographs are the best first step. Look for vertebral height loss or endplate deformities. If red flags are present, or you suspect retropulsion or other complications, escalate to CT or MRI—and refer urgently if needed.

You’ve found one—now what?

If there’s no concern for neurologic deficits or spinal instability, most compression fractures can be managed conservatively.

Start with pain control: acetaminophen or NSAIDs are first-line. Avoid opioids when possible. Bracing may help, ranging from rigid TLSO or Jewett braces to soft corsets. Bracing typically lasts 4–8 weeks, but should be used judiciously to prevent muscle atrophy.

Encourage early mobilization. Prolonged bed rest can lead to deconditioning, DVT, and delayed recovery. Patients should stay active with light ADLs and avoid heavy lifting, deep forward bending, or twisting during the initial healing phase.

Rehab should focus on strengthening the spinal extensors (like the multifidi and erector spinae) to reduce the risk of future fractures. Programs like the Mayo Clinic’s ROPE protocol or aquatic therapy can be great options. Include balance and fall prevention strategies to support long-term safety.

Conclusion

Atraumatic spinal compression fractures are common in older adults, especially postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Recognizing them requires a careful history, targeted physical exam, and appropriate use of imaging. Most are managed conservatively with pain control, bracing, mobilization, and attention to bone health, reserving invasive interventions for selected cases. Addressing the underlying osteoporosis is just as important as managing the fracture itself to prevent future injuries and preserve mobility.

Practice-Changing Education

Experience education that goes beyond theory. Explore Hippo Education’s offerings below.